Does your dog have an annoying habit?

The list of annoying dog habits is potentially a long one:

- Chewing

- Barking

- Jumping up on people

- Getting on furniture

- Begging for food

- Digging in the yard

- Pulling on the leash

- Urine marking

- Separation anxiety

- Anxiety over loud noises or storms

Whew! But today let’s talk about when a dog is licking — until a sore spot forms.

Again, I’m not talking about the occasional slurp.

No, I’m talking today about dog licking that is taken to self-harm levels — where, as a result, the dog develops sores called lick granulomas.

Maybe you’ve seen this: a raised, red sore on a front leg that your dog licks at obsessively. Or perhaps you never seen your dog lick, but the sore is there all the same.

Chances are you told your dog to stop, so they learned to become secretive about licking. Well, these sores are surprisingly common.

Why Your Dog Is Licking Their Leg Constantly

I compare dogs with these sores, lick granulomas, to children who suck their thumb. Once the habit starts, it’s hard to break.

The reason is that the dog licking releases feel-good hormones called endorphins. The dog licks, it feels good, and the dog doesn’t want to stop licking.

We know this because of research into this behavior.

Dr. Nicholas Dodman, BVMS, DACVB, DACVAA, says he became deeply interested in the subject years ago. The condition was then known as acral lick dermatitis, or ALD. Dogs were licking their legs so much that sores developed.

Dr. Dodman and a colleague conducted studies into “this curious self-directed behavior” — and what they found was surprising.

“Our experiments demonstrated that nature’s own morphine-like substances — the endorphins — were involved in ALD, because affected dogs’ self-licking behavior decreased dramatically when the dogs were treated with endorphin antagonists,” Dr. Dodman recounts in his 2008 book The Well-Adjusted Dog.

“Since endorphins are released in stressful situations,” he says, “our results appeared to confirm that stress was involved” in causing the dog licking.

Later studies by a psychiatrist, he says, discovered that the dog licking, also referred to as acral licking, was remarkably similar to human obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) sufferers. The research indicated that “certain large breeds of dog were commonly affected and thus may be genetically inclined to the condition.”

3 Dog Breeds at High Risk of Compulsive Licking

Any dog can become an obsessive licker, but certain larger breeds seem more at risk, including:

Possible Health-Related Causes of the Licking

For most dogs, the habit starts with a trigger in the form of an itch, ache or infection.

Was YOUR Pet Food Recalled?

Check Now: Blue Buffalo • Science Diet • Purina • Wellness • 4health • Canine Carry Outs • Friskies • Taste of the Wild • See 200+ more brands…

It may be that the dog has arthritis or an allergy, and rather than lick the specific spot, the dog chooses a comfortable place to lick — which is often a forearm or paw.

Common triggers:

- Arthritis

- Parasitic infection that causes a general itch

- A bacterial skin infection

- Ringworm

- Skin allergies triggering an itch

According to Dr. Ian B. Spiegel, VMD, DACVD, “More than half of dogs with acral lick dermatitis are suspected to have concurrent fear- or anxiety-based conditions or both (e.g., separation anxiety, noise phobia, anxiety-related aggression).”

Dr. Spiegel adds that this is “one of the most challenging and frustrating” conditions he manages in dogs.

Dr. T.J. Dunn Jr., DVM, agrees, going so far as to call it “a dermatology nightmare.”

“The problem,” Dr. Dunn says, “is that we veterinarians cannot give the owner a specific recipe for a cure…. The skin lesions will heal slightly, almost seem like they are going to heal, [but then] overnight (or during the day while left alone) the lick granuloma is activated” by the dog licking the area raw once again.

Even worse, he says, some dogs will simply switch to licking the other leg if you restrict their ability to lick the first leg by wrapping it in a cast. And “now there are 2 lick granulomas!”

Meet Buster: A Dog Licking So Much That a Sore Spot Forms

One case that springs to mind is that of Buster, an overweight English Springer Spaniel. Buster was an avid licker, and for several months his caregiver had controlled things at home.

The caregiver’s solution was to put a sweatband over the sore, to stop Buster from licking the area.

The only problem is Buster then started onto the opposite leg. When I met Buster, he had sweatbands on all 4 legs — like some bizarre canine tennis player — and he had just started licking his upper arm.

Does Your Dog Do This? If So, Act Quickly.

If your dog starts to lick obsessively, seek the help of your veterinarian.

Getting to the bottom of the cause, and early treatment, is the best way to stop the problem from becoming ingrained.

Alongside treating the lick granuloma, your vet may want to run tests to investigate any underlying problems.

In Buster’s case, his aching joints were at the heart of the matter. Unfortunately, his problem was too well established to stop with arthritis medication alone because the licking had become a reward in its own end.

Treatment of Lick Granulomas in Dogs

Think of this as a 2-pronged attack: tackling both the sores and the underlying cause.

Lick granulomas are frustrating because even with successful treatment, the dog is likely to relapse. To stand any chances of long-term success, therapy must continue for at least 4 weeks after the symptoms have ceased.

Treating the sores:

- Antibiotics or antifungals

- Local anesthetic creams

- Anti-inflammatory medications (to reduce the skin tingle)

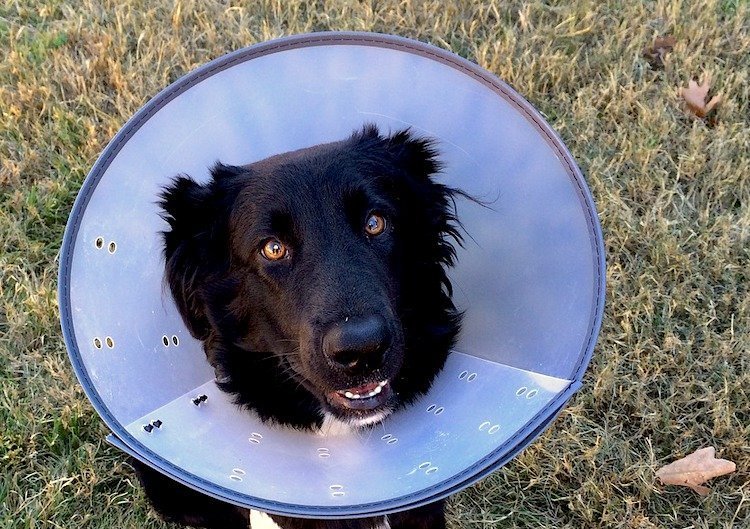

- Bandages or an Elizabethan collar (“cone of shame”)

- Mood-modifying drugs

Your vet may try one or a combination of the treatments above.

Frustratingly, “putting an Elizabethan collar on doesn’t work well,” says Dr. Dunn, “because as soon as it is removed, the licking starts again and the dog will activate the lesion all over again.”

Addressing the underlying triggers:

- The first step is to find out what they are. This could mean blood tests, skin biopsies or radiographs.

- In the case of allergies, starting the dog on a hypoallergenic diet is a great idea, as is testing for environmental allergens.

- Regular parasite treatments against fleas and mites are crucial to keep parasitic itches at bay.

What Happened With Buster?

Arthritis medication alone reduced Buster’s licking but didn’t stop it altogether.

Rather than put Buster on costly drugs that modulate his immune system, or steroids, Buster’s caregiver decided to keep him pain-free with arthritis meds, put him on a diet to reduce his weight, stick with the wristbands and accept a reduced level of licking. This worked well for both of them.

To find the right solution for your dog, speak with your vet.

References

- Dodman, Nicholas H., DVM. The Well-Adjusted Dog: Dr. Dodman’s 7 Steps to Lifelong Health and Happiness for Your Best Friend. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2008. 158–160. https://books.google.com/books?id=5f8aABaBfacC&pg=PA158#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Rapoport, Judith L., MD. “Drug Treatment of Canine Acral Lick: An Animal Model of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.” Archives of General Psychiatry 49, no. 7 (July 1992): 517–521. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1385694.

- Spiegel, Ian B., VMD, DACVD. “Just Ask the Expert: How Do You Combat Acral Lick Dermatitis?” dvm360. Oct. 1, 2010. http://veterinarymedicine.dvm360.com/just-ask-expert-how-do-you-combat-acral-lick-dermatitis.

- Dunn, T.J. Jr., DVM. “Acral Lick Granuloma: A Dermatology Nightmare.” PetMD. https://www.petmd.com/dog/general-health/evr_dg_acral_lick_granuloma_a_dermatology_nightmare.

- Nelson, Richard W., DVM, and Guillermo Couto, DVM. Small Animal Internal Medicine, 4th Edition. Mosby. 2008.

- Shumaker, Amy, DVM, DACVD, et al. “Microbiological and Histopathological Features of Canine Acral Lick Dermatitis.” Veterinary Dermatology 19, no. 5 (October 2008): 288–298. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18699812/.

- Goldberger, Erica and Judith L. Rapoport, MD. “Canine Acral Lick Dermatitis: Response to the Antiobsessional Drug Clomipramine.” Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 27, no. 2 (March/April 1991): 179–182.

This pet health content was written by a veterinarian, Dr. Pippa Elliott, BVMS, MRCVS. It was last reviewed Aug. 7, 2019.

This pet health content was written by a veterinarian, Dr. Pippa Elliott, BVMS, MRCVS. It was last reviewed Aug. 7, 2019.