This pet health content was written by a veterinarian, Dr. Debora Lichtenberg, VMD. It was last reviewed on May 24, 2024

If you have questions or concerns, call your vet, who is best equipped to ensure the health and well-being of your pet. This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. See additional information.

Photo: Wouter van der Vet

Understanding Worms in Cats

Worms in cats can cause significant health issues. Understanding the symptoms of worms in cats, types, and treatments for these parasites is crucial for your pet’s health.

“Worms” — this is actually a common misnomer for gastrointestinal (GI) parasites. That’s because all GI worms are parasites but not all GI parasites are worms.

There are truly only 6 GI parasites common in cats, the first 4 of which are, well, worms.

For comprehensive information on worms in dogs, including hookworms, refer to our detailed article on hookworms in dogs.

Types of Worms in Cats

Roundworms

These worms occur in dogs (Toxocara canis) and cats (Toxocara cati) and are super-obvious spaghetti-looking worms that are highly visible to the naked eye. They are also called ascarids.

Your pet might vomit up a big pile of them or pass a pocketful of them in poop. To top off the yuck factor, they are often moving!

Puppies and kittens routinely get these worms from their mothers. Adult dogs and cats get them from infected feces. And dogs can certainly get them from eating poop.

Rarely, roundworms can infect people. Kids are more at risk because they might be playing in sand or soil with infected fecal matter.

Roundworm infections in people can be very serious. The worm can migrate to the eyes, lungs and other organs. Washing hands and cleaning up all pet excrement safeguards against this rare zoonotic disease.

Tapeworms

Tapeworms (Dipylidium caninum) are little flat worms that you can see in poop, but they’re not as disgusting as roundworms, in my opinion.

To use yet another food analogy, they look like rice — or, for the more discerning palate, orzo.

A tapeworm is a long, flat, off-white worm, but they are segmented. Often, you find only pieces of a tapeworm that look like rice grains in feces or taking up real estate around your pet’s anus, dried up on the fur.

Once in a while, you get to see a long, living tapeworm doing its slinky dance and pulsating out in little segments.

Tapeworms are generally contracted when your dog or cat eats a flea while grooming. The tapeworm eggs are inside the flea but can’t come to full maturity until eaten by a mammal.

Hookworms

Hookworms (Ancylostoma caninum) are very small parasites that infect the small intestine of dogs and sometimes cats.

They attach to the lining of the gut and suck blood, causing mild to severe GI signs.

These parasites also migrate through the lung, but coughing is fairly rare. The majority of damage is typically done in the intestines.

Dogs and cats contract hooks from infected feces in soil.

Hookworms live in the soil and can infect humans by entering the skin, causing a parasitic skin disease called cutaneous larva migrans. This is most common in warmer climates, where people walk on infected soil or beaches with bare feet.

The hookworm does not enter the GI tract of humans.

Giardia

Giardia is a type of protozoan parasite that attaches to cells in the small intestines of many species (dogs, cats and humans), which leads to maldigestion, malabsorption and diarrhea.

Pet-to-human transmission of giardia is quite rare. People are usually affected after drinking infected water, not from their pet.

Giardia is not easily seen on a regular fecal exam. If it is suspected, we can run a more specialized stool check with centrifugation. A reliable ELISA test is now available as well. Any of these tests require a small amount of fresh stool.

Coccidia

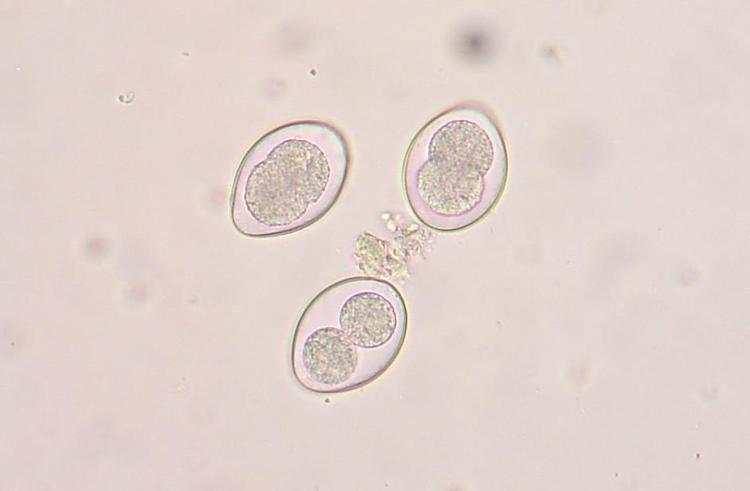

Coccidia (Isospora) are microscopic intracellular parasites.

We can find immature coccidia (oocyst) microscopically on a fecal exam.

Coccidia can cause young animals and immunocompromised individuals to have diarrhea, sometimes severe. The oocysts can be difficult to eradicate in the environment, particularly in a large kennel, shelter, or boarding facility.

Symptoms of Worms in Cats

Recognizing Symptoms

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Gas

- Abdominal pain

- Pot-bellied appearance in young animals

- Foul-smelling poop

- GI blood loss leading to anemia

- Damage to the GI tract causing a malabsorption or low protein syndrome (hypoproteinemia)

- Cough (some stages of parasites migrate through the lungs before hitting their final destination in the gut)

- Unthrifty appearance

Diagnosing Worms in Cats

Although some worms in cats can be identified visually (roundworms and tapeworms), a stool specimen is required to diagnose GI parasites correctly and thoroughly.

Let’s start with the all-important fecal sample — the bag of poop you bring to your vet for the annual physical:

- A small amount is all you need to bring. Think sample size — no super-sizing of the poop sample, please.

- You may be asked to scoop the poop at other times too and bring us a small sample, particularly when your pet is having diarrhea.

In a routine stool sample, we float the poop in a solution that allows the parasite eggs to float to the top. Then we mount a drop of the sample on a slide and look for the eggs under a microscope.

We can identify parasites by the shape of their eggs. With the parasite identified, we can prescribe the proper drug and “deworm” the pet. There are other, more esoteric tests we can run on poop if we suspect uncommon parasites or pathogens.

By flotation or centrifugation in a special solution, parasitic eggs, larvae, or protozoal cysts in the fecal sample will be separated from the feces.

We then analyze this sediment under the microscope and identify parasites by the shape and character of the eggs or cysts.

Deworming

Deworming Medications

- Anthelmintics: These drugs are used to treat parasitic worm infections. It’s essential to identify the specific parasite to choose the correct medication.

- Treatment Frequency: Most treatments require multiple doses to address the parasite’s life cycle effectively.

Treating Worms

Prescription Medications

Prescription dewormers are tailored to the specific parasite and administered according to a vet’s guidance. These are often more effective than OTC products.

Over-the-counter (OTC) Products

There are safe and effective deworming products that you can buy yourself, such as fenbendazole, a dewormer that used to be available only through a veterinarian.

It’s important, however, to know what parasite you’re treating, how your pet got them, how many times to give the medication, and what to do to prevent re-infection.

Fenbendazole, for example, is effective against tapeworms, roundworms, hookworms and whipworms, but dosing should be carefully formulated for the animal’s weight, and the follow-up care is essential.

On the package of one generic fenbendazole product called safe-guard®, for instance, the company claims its product, if administered for 3 consecutive days, is completely effective for up to 6 months. This is misleading.

Fenbendazole is generally not considered to be effective as a one-time treatment:

- Roundworms and hookworms should be re-treated within a few weeks.

- Whipworms should be re-treated in several months.

- And tapeworms? The one-time treatment fenbendazole is effective, but if you don’t get rid of the fleas that most likely caused the tapeworm infection, your pet will probably get tapeworms again. Then you’ll think the medication failed when actually the lack of flea treatment is the cause of the re-infection.

If you buy an OTC wormer, please call your vet to get specific instructions to make sure you’re using the proper product.

Under-dosing or not repeating the dose at the proper interval can lead to your pet always living with a low level of parasites.

Was YOUR Pet Food Recalled?

Check Now: Blue Buffalo • Science Diet • Purina • Wellness • 4health • Canine Carry Outs • Friskies • Taste of the Wild • See 200+ more brands…

Preventing and Managing GI Parasites

Regular stool sample analysis and heartworm preventive measures can help maintain your cat’s health. It’s essential to follow your vet’s advice on treatment schedules and preventive care.

Untreated GI Parasites

Untreated parasites can cause severe health issues, including anemia, malnutrition, and potentially fatal complications. Regular vet check-ups and preventive measures are vital.

Additional Considerations

Empiric Deworming

Empiric deworming means you give your pet a safe deworming medication if you suspect intestinal parasites (worms), even if your vet hasn’t found actual evidence of the worms in a stool sample.

The most common reasons to do this are:

- There is a history of recurrent worms found in a pet or a household.

- You can’t supply the vet with a reliable stool sample.

- If a pet has recurrent or intractable diarrhea but multiple stool samples don’t reveal any parasites, it’s perfectly acceptable to give a broad-spectrum wormer to treat worms that cannot be found.

Say a dog or cat has intractable diarrhea, is not responding to diet trials and various medications, and has negative stool samples. In these cases, it’s not only acceptable but recommended to empirically deworm the pet. We suspect worms but can’t find them.

We also suggest deworming puppies, kittens, stray animals, and pets who spend a great amount of time outdoors roaming.

People often ask why I couldn’t find worms in their cats. The simplest answer is that parasites are sneaky pests that don’t show up in all samples. Parasites don’t like:

- Old poop (rock poop)

- Frozen poop (poopsicles)

- Icky poop (watery poop)

Vets must pay attention to the shelf life and quality of your pet’s poop. Some parasites shed intermittently, so your vet might ask you to collect stool samples 3 days in a row.

Stool Sample Importance

Identifying specific parasites through stool samples allows for more effective treatment and helps prevent re-infection.

A Note on Maggots

Maggots top tapeworms on the gross-out scale, in my opinion. People might confuse maggots and tapeworms, but they look very different:

- They are larger than tapes, and there are usually a lot of them.

- Also, maggots hatch on top of the poop from fly larvae in hot weather.

- They are never apparent when your dog poops.

If you ever find maggots on your cat, see your vet right away. Your vet will most likely find a wound or sore or matted fur that’s been colonized by fly eggs — and maggots have developed.

Your pet will need professional wound care and antibiotics.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are the symptoms of worms in cats?

The symptoms of worms in cats include diarrhea, vomiting, weight loss, a pot-bellied appearance, and a dull coat.

What happens if a cat goes untreated for worms?

If a cat goes untreated for worms, it can suffer from severe health issues such as malnutrition, anemia, intestinal blockage, and in extreme cases, death.

How did my indoor cat get worms?

Your indoor cat can get worms by ingesting eggs or larvae brought in on your shoes or other pets, through fleas that carry worm larvae, or from infected prey like mice.

References

- Bowman, Dwight, PhD. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians, 10th ed. Saunders. 2013.

- Burke, Anna. “Whipworms in Dogs.” American Kennel Club. June 7, 2017. https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/health/whipworms-dogs-symptoms-treatment-prevention/.

- “Gastrointestinal Parasites in Dogs.” VetFolio. http://www.vetfolio.com/gastroenterology/gastrointestinal-parasites-in-dogs.

- Zajac, Anne, et al. Veterinary Clinical Parasitology, 8th ed. Wiley-Blackwell. 2012.