The Evanger’s recalls of 2017 — first on Feb. 3 and later expanded on Feb. 28 — left many pet lovers reeling.

Dog food recalls are one thing, but what was so horrifying about this one was the nature of the possible contaminant: a barbiturate called pentobarbital, which doubles as a euthanasia drug.

Here’s our exhaustive 3-part report on the recalls and the fallout.

Part 1: A Dog Dies and the Recalls Begin

On New Year’s Eve, Washington resident Nikki Mael says she fed her 4 pugs a can of Evanger’s Hunk of Beef Au Jus as a treat. Within minutes, all 4 dogs were exhibiting alarming symptoms, and Mael rushed them to the veterinarian.

Tragically, one of her pugs, Talula, died. Another pug was still experiencing seizures, Mael said. A necropsy determined that Talula may have overdosed on pentobarbital.

Let’s take a closer look at what’s happened since and try to address the biggest question of all: How could a powerful sedative used for euthanization have possibly made its way into this pet food?

Evanger’s Recall Response

By most accounts, Evanger’s took a proactive and transparent stance on the incident with the pugs.

Within the first 48 hours, the company had reached out to Mael. It then traced, found and sent cans from the same lot that Mael’s can came from for testing and posted on its website about the situation to let customers know about the potential problem.

Evanger’s posted frequent updates, including test results as they trickled in, and was responsive to consumers on social media.

“This is a very challenging time, but we welcome any opportunity to connect and offer transparency and information,” spokesperson Erin Terjensen said in an interview with Petful.

How Could It Happen?

After the first recall on Feb. 3, 2017, Evanger’s said the pentobarbital could have made its way into the food via beef from Evanger’s supplier.

The company also blamed lax regulations by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

In this video, Brett and Chelsea Sher, whose family owns and operates Evanger’s, addressed the recall:

“Ultimately, what this comes down to is we feel that there is a lack of regulation, which in turn made our supplier let us down, and in turn it’s our name on the label and we let the public down,” Chelsea Sher said in the video.

But was that really the case?

The FDA Drops a Bombshell

Two weeks after the initial Evanger’s recall on Feb. 3, the FDA dropped a bombshell in the Evanger’s recall case.

Here’s what Evanger’s Dog & Cat Food Company had been boldly proclaiming on its own website:

Was YOUR Pet Food Recalled?

Check Now: Blue Buffalo • Science Diet • Purina • Wellness • 4health • Canine Carry Outs • Friskies • Taste of the Wild • See 200+ more brands…

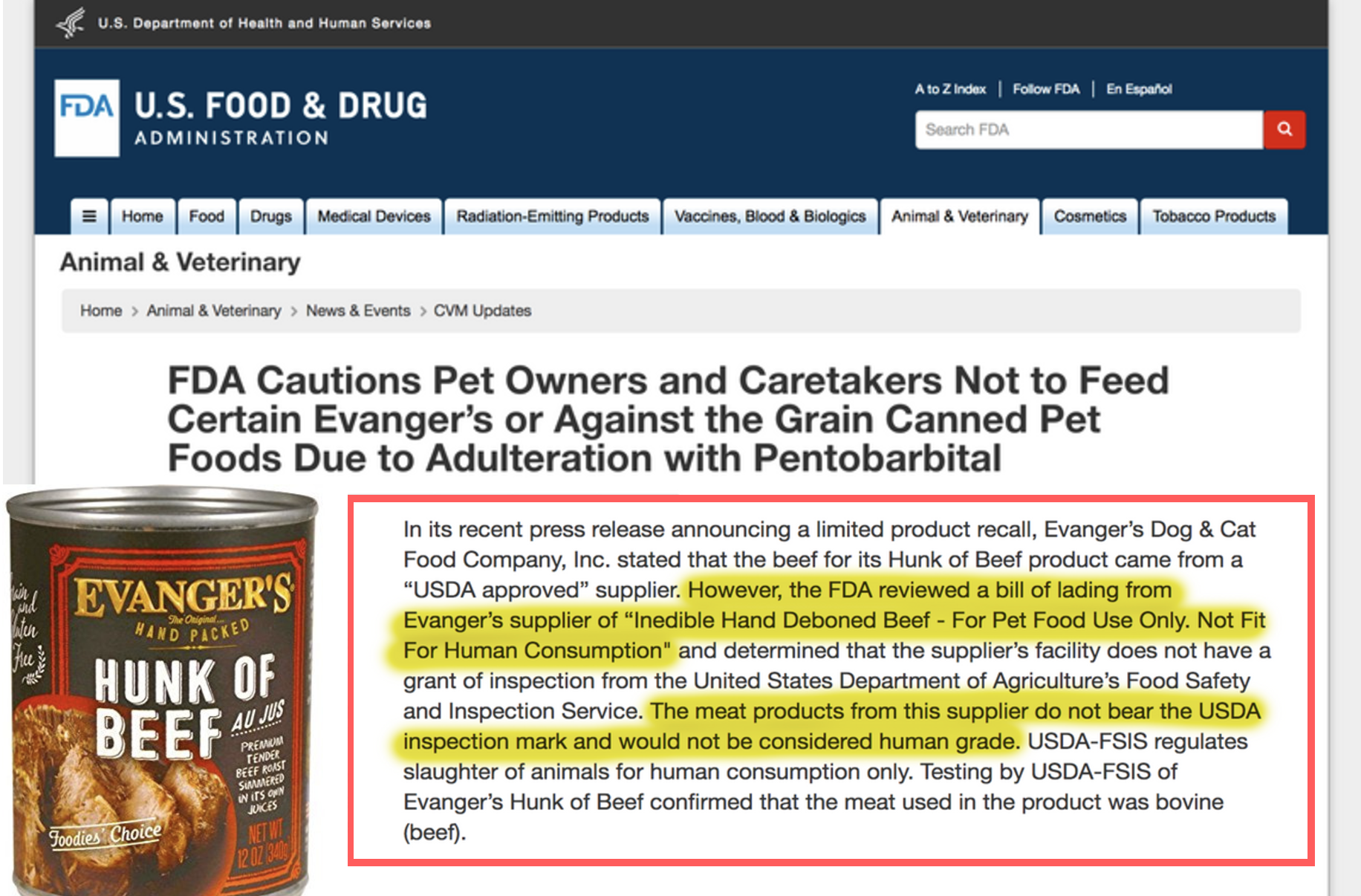

“We take a tremendous amount of joy and pride in manufacturing what we truly believe is the best pet food in the world…. Evanger’s utilizes human-grade USDA inspected meats….”

And here’s what the company said in a press release announcing that its Hunk of Beef dog food formula had been recalled:

“All Evanger’s suppliers of meat products are USDA approved. [Cows] are slaughtered in a USDA facility.”

The only problem? The FDA now said this was nonsense.

In a startling rebuttal on Feb. 17, the agency released a letter of caution today that directly called out Evanger’s. The FDA said its inspectors had seen with their own eyes a receipt demonstrating that Evanger’s supplier was providing meat that was “inedible” and “not fit for human consumption.”

Not only that, but the supplier, in fact, had no USDA association.

“The meat products from this supplier do not bear the USDA inspection mark and would not be considered human grade,” the agency wrote.

The FDA told us its own tests had definitively confirmed the presence of pentobarbital — a drug used for euthanasia in animals — in unopened cans of both Evanger’s and Against the Grain canned dog food from specific lots. That’s a direct link from the food to the now-deceased pug whose stomach contained pentobarbital, according to necropsy results.

“Pentobarbital is a drug that is used in animal euthanasia. It should not be in pet food,” the FDA said in its caution letter.

It Gets Worse

Even with all that bad news, things only got worse for Evanger’s.

The FDA mentioned as well that its recent inspections of the pet food maker’s 2 manufacturing facilities in Illinois didn’t go very smoothly, pointing out “numerous” and “significant” concerns about the conditions there.

Inspection reports revealed peeling paint and mold on the walls, as well as condensate that was “dripping directly into open cans of … Hunk of Beef, and also into multiple open totes of raw meats.”

In other words, gross stuff on the ceilings was dripping directly onto the food, as inspectors watched on in astonishment.

- There also was no refrigerated storage of raw meats in one of the facilities, according to the inspection reports.

- Raw meat was being prepared “while having direct contact with the insanitary, bare, paint peeling and unprotected concrete floor of the processing facility.”

- In addition, the FDA noted a “live fly-like insect” in an area where dog food was being packed. And birds were seen congregating in the rafters above and eating spilled pet food on the floor.

This was, needless to say, a devastating report for Evanger’s, one that opened the company up to potential lawsuits stemming from the recalls.

Hunk of Beef was Evanger’s best-selling product, with more than 1 million cans sold per year.

The Unthinkable

It had long been speculated that euthanized animals — including dogs and cats — have made their way into pet foods.

In 2002, the FDA received so many reports from vets claiming that their patients were developing a resistance to pentobarbital that a study was conducted to find out how animals were affected by the drug.

The study resulted in 3 important findings:

- Although pentobarbital was, in fact, found to be in pet foods, it was at an extremely low level.

- No dog or cat remains were found in any tested samples.

- The presence of the pentobarbital was attributed to euthanized cattle and/or horses.

“It seems extraordinarily unlikely that the pentobarbital originated from euthanized pets,” said Dr. Pippa Elliott, BVMS, MRCVS, a veterinary writer for Petful.

“On a practical level, by law, disposal of animal carcasses is strictly controlled and monitored, making the possibility of pets entering the food chain extremely remote.”

Except in cases of animal health emergencies, euthanasia is not a practical method for slaughtering cattle. Most slaughterhouses use cheaper and more effective methods for day-to-day operations.

The Supplier

Evanger’s supplier remained unnamed because of potential litigation issues.

However, Evanger’s said it was no longer using the supplier. “Once we learned the word ‘pentobarbital’ on Sunday — done with that supplier,” Chelsea Sher said in the video. “Never buying from him again.”

Evanger’s Promises

This was the first recall in Evanger’s 82-year history. What was the company doing to ensure that something like this didn’t happen again?

“What we’re doing going forward to ensure the safety of our products is testing every single lot of hand-packed beef products that comes out of our facility, and we will not release any of that product into the public until it has been cleared by testing,” said Chelsea Sher.

Evanger’s also vowed to fight for better regulation surrounding barbiturates in the pet food supply chain.

Part 2: A Decade of Problems Led Up to 2017 Evanger’s Recalls

Until the 2017 recalls, Evanger’s had stood proud of its 82-year recall-free history.

But recalls aren’t the whole story when it comes to pet food manufacturing. A lot of other issues can affect the food and yet a company can remain technically “recall-free.”

Evanger’s management team liked to talk about how the company had been “family-owned and operated” since 1935. But the owners of 2017 had only been around since 2002. And that’s pretty much when the wheels started coming off the bus.

The Plant

2006: Sued by the Town

Four years after Holly and Joel Sher purchased Evanger’s, residents of Wheeling, Illinois, had plenty to say to local health officials about conditions at the manufacturing facility.

“Throughout the summer of 2006, the Village of Wheeling alleged they received numerous odor complaints emanating from Evanger’s production of dog and cat food,” the Better Business Bureau notes.

“The Village issued citations to Evanger’s on August 24, 2006, for violating several ordinances. The citations alleged: failure to provide tight-fitting garbage can lids, containers of food and waste not covered with tight fitting lids, failure to provide approved containers, food waste held in unapproved containers, failure to remove refuse, accumulation of refuse stored on exterior property, and failure to abate stagnant water accumulated on exterior property.”

This kicked off a long legal battle.

Several residents and local officials testified about allegedly bad odors and unsanitary conditions.

A health inspector said she “observed open containers of chicken, flies, maggots, refuse and unsanitary conditions on the property,” according to court documents. She also claimed to have noticed a “strong rotting meat smell.”

Another health inspector testified that, months later, she observed “‘thousands’ of maggots on rotten decaying animal parts; flies and maggots over unknown rotting substances.”

As the lawsuit made its way through the courts and the appeals process, the smell allegedly coming from the plant didn’t go away, according to residents.

- A summer camp for kids had to be moved.

- Organizers said outdoor concerts at a nearby park were marred by numerous complaints about the odor, which was said to be “coming from the direction of Evanger’s.”

2008: FDA Requires Emergency Permit

On April 24, 2008, the FDA issued an order “requiring that Evanger’s … obtain an emergency permit from the agency before its canned pet food products enter interstate commerce.”

The order was issued after an inspection found:

“…significant deviations from prescribed documentation of processes, equipment, and recordkeeping in the production of the company’s thermally processed low acid canned food (LACF) products. These problems could result in under-processed pet foods, which can allow the survival and growth of Clostridium botulinum (C. botulinum), a bacterium that causes botulism in some animals as well as in humans.”

Holly Sher told reporters that the FDA’s comments were “highly inaccurate and misleading.”

In June 2008, the FDA approved a temporary emergency permit after being satisfied that Evanger’s had remedied the issues.

2009: Emergency Permit Revoked

Between March and April 2009, the FDA continued to monitor and inspect the Wheeling plant.

Then, in June 2009, as a result of those inspections, the emergency permit was revoked.

“The FDA is stopping Evanger’s ability to ship pet food in interstate commerce,” said Dr. Bernadette Dunham, director of the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine.

“Today’s enforcement action sends a strong message to manufacturers of pet food that we will take whatever action necessary to keep unsafe products from reaching consumers.”

2011: Adulterated Product and Missing Records

In May 2011, a warning letter sent by the FDA to Evanger’s detailed violations found during a 2-month inspection of the company’s manufacturing plant as well as in a sample of dog food obtained from the distributor.

In a nutshell, the product was shown to be adulterated, the agency said.

The FDA explained exactly what it meant by “adulterated”:

“Under Section 402(b)(2) of the FD&C Act, 21 U.S.C. § 342(b)(2), a food is deemed to be adulterated if any substance has been substituted wholly or in part therefore.”

Testing found that a Lamb and Rice mix actually contained beef rather than lamb, and a duck pet food actually had no duck at all.

Two years later, the FDA sent a closeout letter to Evanger’s, stating that the violations appeared to have been addressed, but warning that this did not “relieve you or your firm from the responsibility of taking all necessary steps to assure sustained compliance with the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and its implementing regulations or with other relevant legal authority. The Agency expects you and your firm to maintain compliance and will continue to monitor your state of compliance.”

2011: A Slew of Sanitation Citations

On Dec. 5, 2011, Evanger’s was cited for a number of health and sanitation issues by the FDA, including:

- Failure to provide adequate screening or other protection against pests.

- Failure to manufacture and store foods under conditions and controls necessary to minimize the potential for growth of microorganisms.

- Failure to thaw frozen raw materials in a manner that prevents them and other ingredients from becoming adulterated.

- Instruments used for measuring conditions that control or prevent the growth of undesirable microorganisms are not accurate.

- Failure to provide adequate lighting in areas where food is examined, stored, or processed.

- The plant is not constructed in such a manner as to prevent drip and condensate from contaminating food, food-contact surfaces, and food-packaging materials.

- Failure to clean food-contact surfaces as frequently as necessary to protect against contamination of food.

- Failure to use water which is safe in food and on food-contact surfaces.

- Failure to maintain toilet facilities in a sanitary condition.

- Failure to provide hand washing facilities at each location in the plant where needed.

2012: More Citations

On Nov. 14, 2012, the FDA returned to conduct another inspection.

Once again, myriad violations were found — and some were uncorrected from the previous inspection. One example: “Failure to provide adequate screening or other protection against pests.”

The FDA also cited Evanger’s for “Failure to store foods under conditions and controls necessary to minimize contamination.”

The Owners

The plant wasn’t the only problem the Shers were facing. They apparently created some issues of their own.

2010: Utility Theft Arrests

In March 2010, news reports surfaced that Holly and Joel Sher, owners of Evanger’s, had been arrested and were accused of stealing almost $2 million in utilities for their manufacturing plant.

The couple allegedly put their employees at risk by having them do the diversion work.

According to the Chicago Tribune, one employee was allegedly made to don rubber gloves and go up on a forklift to remove an illegal electricity bypass from a pole before an inspection. Another was allegedly made to jackhammer up concrete and asphalt to divert gas to the plant.

“The brazen nature of these thefts is exceeded only by the dangerous conditions that these individuals were willing to expose their employees to,” Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez told the Tribune.

2013: Bribery Charges

In 2013, while the above case was still open and ongoing, Joel Sher was again arrested, this time charged with trying to bribe a witness in that case.

According to the Tribune, Sher “allegedly offered $5,000 to a witness in exchange for changing testimony.”

Where There Was Smoke, There Was Fire

In short, there was plenty of smoke over the past decade, leading up to a fire that was now roaring in February 2017.

One dog was dead after eating pet food that contained pentobarbital.

The dog’s human, Nikki Mael, had thought she was feeding some of the best stuff on the market — human-grade, USDA-inspected “People Food for Pets” — but she had ended up apparently euthanizing her own pet with that very food.

In the days to come, yet more details would emerge that would finally begin to shed light on how, exactly, a euthanasia drug ended up in cans of dog food.

Part 3: Horse DNA Found in “100% Beef” Evanger’s Pet Food

On Feb. 20, 2017 — just 3 days after the FDA’s blistering caution letter about Evanger’s — The Columbian newspaper of Vancouver, Washington, dropped a shocking report.

The newspaper reported that horse DNA had been discovered in tested samples of Evanger’s Hunk of Beef canned dog food.

How could this be?

Hunk of Beef had marketed as an all-beef product. In fact, the only ingredient listed on the can was “100% Whole Beef Cooked In Its Own Juices.”

“The company sent the food out for DNA analysis, and the results showed beef, as well as horse DNA,” the newspaper said Evanger’s co-owner Joel Sher stated in an interview.

The testing had been ordered by the company itself after Nikki Mael’s dog died.

Oddly enough, earlier testing by the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service, at the request of the FDA, did not find anything except bovine DNA (beef).

The FDA’s investigation continued, and Evanger’s blamed one of its suppliers for the adulterated pet food, saying the supplier has since been fired.

Update, May 2018: FDA Concludes Evanger’s Investigation, Company Sues Meat Supplier

Stay on Top of Pet Food Recalls

If you have not done so already, we urge you to sign up now for Petful’s FREE recall alerts by email. Our free alerts are saving pets’ lives.