Think your dog might have a urinary tract infection (UTI)?

These types of infections are common in dogs — but they can be simple or complicated.

Don’t ignore any changes in your dog’s urination habits. The longer you wait to address a UTI, the harder it will be to cure.

Also, please remember that cat urinary problems are unique, so don’t read this article and think the info applies to cats. It does not.

Signs and Symptoms

Here are the common canine UTI scenarios:

- “My dog went for a normal walk but peed 5–6 times on our walk. Then she squatted and nothing came out.”

- “I noticed my dog has been urinating more than usual, and I think the urine looked a little pink.”

- “My dog peed on the snow, and it’s red!”

- “My dog is peeing in the house all of a sudden, and she’s licking herself.”

8 most common signs/symptoms that a dog might have a urinary tract infection:

- Frequent urination

- Straining to urinate

- Blood in the urine

- Licking the genitals

- Discomfort or vocalization when urinating

- Loss of house-training

- Strong odor or color change in the urine

- Increased thirst

The most common causes of a UTI:

- Bacteria in the urinary tract

- Bladder stones

- Tumors of the bladder or urinary tract

- Structural abnormalities in the urogenital tract

- Diseases such as diabetes mellitus or Cushing’s syndrome

- Medications such as prednisone that suppress the immune system

- Prostate problems in male dogs (bacterial prostatitis)

Who is more at risk for developing a UTI?

- Female dogs

- Older dogs

- Female dogs with inverted vulvas

- Breeds susceptible to bladder stones

- Intact male dogs (not neutered)

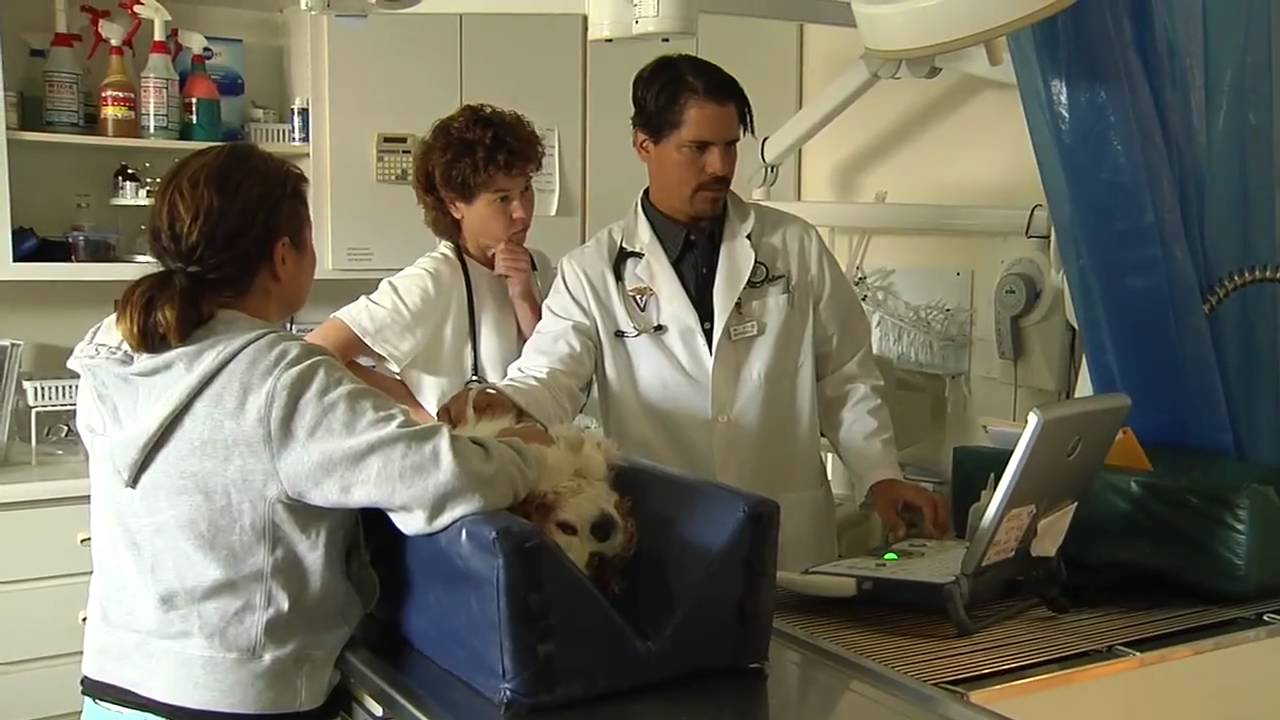

Diagnosing a UTI in a Dog

Everything starts with a urine sample.

A urinalysis is the first step and gold standard in diagnosing a UTI in a dog.

If you notice any of the above signs that your dog might have a urinary tract infection or are at all concerned about your dog’s changes in urination, your veterinarian might ask you to bring in a urine sample when you come in for your appointment. Otherwise, they will get the sample at the hospital.

There are many vets who don’t want a urine specimen collected at home. The gold standard is for your vet to always get a sterile urine sample directly from the bladder. More on this later.

Getting the Urine Sample at Home

Many people balk at this idea, saying it’s impossible to take a urine sample from their dog.

It’s not. It’s easier than you think for most folks!

Try to get your sample during the first potty outing in the morning. Your dog will need to urinate and should have a fairly large volume. This makes collection easier. The first urine of the day may also be of higher diagnostic value to your vet.

Have a clean, dry (does not need to be sterile) container at the ready. Shallow containers work best for females so you can scoot it underneath. Disposable plastic containers work great. They are inexpensive and come with a lid.

Occasionally folks bring me a urine sample and ask for the container back. This is a bit of a nuisance.

Not only might the lab tech throw the container away as soon as she extracts the urine sample, but what are you going to use that container for after you associate it with a pee sample?

More tips:

- Wear a glove while collecting if you have a low gross-out threshold.

- Commandeer a family member to help. One person walks while the other person retrieves.

- We don’t need a lot of urine. Even if you miss the beginning as your dog squats, chances are you will get enough — a tablespoon or so — if you catch any part of active urination.

- A deeper container may help you with a male dog if he is a high leg-lifter with a fairly strong stream.

Getting the Urine Sample at the Vet’s Office

There is a subset of dogs that make getting a urine sample exasperating. If you have tried and tried and failed, chances are your vet staff will be able to help you.

Was YOUR Pet Food Recalled?

Check Now: Blue Buffalo • Science Diet • Purina • Wellness • 4health • Canine Carry Outs • Friskies • Taste of the Wild • See 200+ more brands…

Don’t let your dog urinate on the way to the vet. You might even leave your dog in the car and go into the office and ask for a vet tech’s assistance.

There are many smells at the vet, and your dog might deliver that cherished sample on the way in the door, missing another golden opportunity.

If the vet tech is also unable to get a sample right away, there are a few options:

- You can leave your dog a the office for a few hours until their bladder is full again.

- Or your vet might suggest getting a sample directly from your dog’s bladder. This is called a cystocentesis.

Cystocentesis

The best urine sample is one that is collected directly from the bladder via a needle — a cystocentesis.

Second best is a catheterized sample, which is fairly easy in male dogs but quite difficult in females. You can’t really catheterize a female dog without some kind of sedation.

Inserting a needle directly into the bladder sounds horrible to some folks, but it is usually simple, nontraumatic and over in about 5 seconds. This is also the only way to get an absolutely sterile sample, which is needed for certain urinalyses.

The Urinalysis

Your vet will do a basic urinalysis on the sample, and this will render a lot of information.

Depending on the vet practice, this will either be done in-house and results will be ready very soon, or the sample will be sent out to a vet lab and results will be back the following day.

A basic urinalysis is extremely informative. It includes the following tests:

- The urine dipstick checks for various parameters such as the amount of glucose in the urine (diabetes), pH and protein, for example. These look like the dipsticks you might use in your pool or hot tub.

- The urine specific gravity is a number that is measured with a refractometer. This number tells us how concentrated the urine is. A dilute urine means your dog is thirstier than usual and/or is not concentrating their urine due to a possible kidney function problem or other systemic disease such as Cushing’s syndrome.

- The urine sediment gives us a bird’s-eye view into what cells and other elements are actually floating around in your dog’s urine. A small amount of urine is spun down in a centrifuge leaving the sediment at the bottom of the test tube. That sediment is stained and analyzed under a microscope.

The microscopic urine sediment reveals any red blood cells, white blood cells, bacteria, crystals and any abnormal cells from the bladder.

The sediment tells us a great deal about whether or not an infection is present, what kind of crystals are present and whether something more sinister than a simple UTI might be going on.

Urine Culture and Sensitivity

A urine culture tells us what specific bacteria are growing in the bladder when there is an infection. The sensitivity tells us which antibiotic(s) is the best choice to combat that bacteria.

Getting the urine directly from the bladder via cystocentesis is required to get the best results for a urine culture.

When the basic urinalysis indicates an infection, the culture can put an actual name on that infection, say E.coli, for example. The sensitivity tells us which antibiotic is the best choice to combat that particular E.coli bug.

Additional Testing

An uncomplicated UTI may go away with 1–2 courses of antibiotics and not return. If this is the case, no further testing is warranted.

But if a UTI keeps coming back (refractory) or does not improve with antibiotics (resistant), further testing must be done. These could include radiographs, ultrasound or other advanced imaging of the bladder, cystoscopy, specific tests to measure protein in the urine, additional urinalyses and cultures.

If a bladder tumor is suspected, biopsy and surgery are indicated.

Here’s a quick video with some more information:

Treatment of UTIs in a Dog

Antibiotics are indicated for bacterial UTIs. Prescription food may be required to combat crystals/stones in the urinary tract.

Resistant or recurrent UTIs are a real pain in the neck for the patient, pet parent and doc! Many of these require additional testing before a treatment plan can be reached.

Over-the-county remedies and supplements such as cranberry juice extracts don’t seem to do much good. One of the most trusted voices in holistic/naturopathic veterinary medicine, Dr. Susan Wynn, DVM, CVA, CVCH, AHG, says she does not use them.

The Frustration of Urinary Tract Infections in Dogs

A number of cases will turn into refractory or resistant problems, meaning the UTI just keeps coming back and back.

Take Flossie, for example, a 9-year-old, 50-pound female spayed dog.

Flossie is healthy and athletic, but her human sees bloody urine and Flossie starts to strain to urinate every few months. Flossie “always gets better” on a 10–14 course of antibiotics. Flossie’s mom has some financial difficulties and doesn’t always bring back a urine sample once the antibiotics are finished and has declined culture and sensitivity testing, radiographs, etc.

Although it’s possible that Flossie is simply prone to recurrent UTIs and may need 3 courses of antibiotics a year for the rest of her life, there may indeed be underlying reasons for Flossie’s UTI problem, and further testing is required to get the correct diagnosis.

Although appropriate antibiotic therapy is helpful and makes Flossie feel better, they might stop working. Flossie’s infection might travel to her kidneys (pyelonephritis); she might develop a serious, resistant UTI; or she might have a concurrent underlying problem that is going to get worse.

If your dog has recurrent urinary tract infections, doing the recommended follow-up and further testing earlier rather than later gives your pet a better chance of a solution and a happy, healthy life.

References

- Adams, Larry G., DVM, PhD, DACVIM. “Management of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections.” Pacific Veterinary Conference. 2016.

- Ettinger, Stephen, DVM, DACVIM, and Edward C. Feldman, DVM, DACVIM. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 7th ed. Saunders, 2010.

- Sykes, Jane E., BVSc (Hons), PhD, DACVIM. “Update on the International Guidelines on UTI.” World Small Animal Veterinary Association Congress Proceedings. 2017.

- “Recurrent UTIs: Use of Cranberry Extract.” VIN. 2016-2019.

This pet health content was written by a veterinarian, Dr. Debora Lichtenberg, VMD. It was last reviewed April 16, 2019.

This pet health content was written by a veterinarian, Dr. Debora Lichtenberg, VMD. It was last reviewed April 16, 2019.